There is a strange sense of ambivalence when buying an airplane, knowing that someday you’ll replace almost everything except the aluminum. You want something safe to fly, but an extensive prebuy inspection seems overkill as the expensive surprise awaiting you will not be a surprise. Such was the sense when I bought N7873P in August 2015. “The Beast,” as I lovingly refer to my 1962 250, had several thoughtful owners in the past. One installed a Century IIB autopilot, center stack panel, Strike Finder, Garmin 430, and a Narco DME. Prior to those additions, the paint and interior were updated as well. The gentleman I bought it from was an A&P with too many airplanes in his fleet. The Beast was wearing its age with that paint and interior faded and worn and most avionics not working well. The engine was well past TBO after two field overhauls and the original Hartzell prop was coming due for its AD, but at least it had new main landing gear conduits. In other words, it was perfect.

The prebuy test flight was exciting since, among other things, I wanted to flip on the “inop” autopilot to see if the roll servo was alive. It was, but I scared the owner in the process as the plane rolled steeply to the left. Having extensive experience flying and maintaining my first Comanche 250 long ago, I felt comfortable with everything I saw, but I knew a long-term gut job was ahead of me. The logbooks were complete revealing a few skeletons, like a new right-wing in 1964 after a truck ran into it and a bird strike repair to the same wing with a fancy rattle can paint job.

Standing on the ramp, I asked the owner how he used the airplane. He said he flew his young grandson VFR from Winston Salem, NC, to Richmond, VA, and back with some regularity. That sealed it. All indications were ‘73P was a safe Comanche with good bones. When I told him I was interested in the purchase he said, “What will it take for you to buy it now?” After a long pause rubbing my chin, I owned a cheap, safe Comanche ready for a flying restoration.

The first thing I did once in my possession was pop off the glare shield to see why the autopilot and the Strike Finder didn’t work. I saw the Amphenol connector to the attitude indicator for roll position dangling free in the rats’ nest behind the panel. I reconnected it. I also saw the Strike Finder cable had fallen off the back of the unit. I reconnected that. I now had a cheap, safe Comanche with a functioning autopilot and Strike Finder. This was going well.

After flying around the mountains and farmlands of the upstate of South Carolina, it was time to invest in avionics I could rely on for flying in the clouds and getting where I needed to go. I called Jonathan at Horizon Avionics, a Garmin dealer, to discuss my options. Having cut my IFR teeth on dual VORs, I opted to upgrade the 430 to WAAS, remove the DME, and install a new PMA 6000 audio panel. I added a refurbished King Com and a separate King Nav with glideslope and an ADSB-out Garmin transponder. Not expensive and plenty good with reliable redundancy, especially with the capability of a portable ADS-B in receiver and Foreflight. With a smooth engine, sound compression, low oil consumption, and WAAS, I was comfortable flying through the variable east coast weather.

A few months later, and not having spent a huge sum of money on the Beast yet, the Hartzell prop AD came due. The last time I faced this AD on my first Comanche, I replaced the prop with a McCauley 3-blade Blackmac. This time I felt the need for super modern technology and opted for an expensive MT 3-blade composite propeller and matching governor because … you only do this once. I could detect better climb, lower noise, and Rotax-like start-up and shut down from the low rotational inertia of the MT. The Beast was no longer cheap, but it sported new cool tech, and the large spinner gave it some ramp appeal that diverted attention from the worn and chalky paint. I started flying extensively to Naples, FL, and up to Westchester, NY, from Greenville, SC, with confidence that the high-time engine would give me some early warning when it was time for replacement. It did while climbing directly over Central Park, NYC.

On a sunny Sunday morning in June of 2018 departing Westchester, NY, I received a rare PROP ONE Direct JFK transition SID to start my flight down the coast. Five minutes into my climb, turning over Manhattan and enjoying the view of Central Park, I pulled the prop control back for a cruise climb, and the prop did not respond. Uh-oh. I tried again. No response. The better part of valor is doing nothing for a bit or something like that. I thought through the propeller system. The cable could have failed; the prop seal could have failed; the new governor could have failed, or something in the engine driving the governor could have failed. I saw no oil leaks, oil temperature and pressure were green, the engine was smooth as silk, just the prop was humming at 2575 rpm. I pulled the throttle back until I got 2400 rpm. I was surprised by how much the manifold pressure went down. I was now flying slowly. Ninety knots, to be exact.I almost keyed New York approach and call Pan Pan Pan. But the thought of those ramifications made me pause longer. Flying is all about calculating risk and assessing it against your personal minimums. The weather was great VFR and I could see New Jersey with plenty of altitude, fuel, and stable oil indications. I could climb but my cruise speed was slow. There were several airports ahead of me if things soured slowly or quickly. From the cockpit, it seemed like the prop cable broke, and a repair on a Sunday in NYC was unlikely. The risk was acceptable to me, so I updated ATC and kept my hands off the power controls. What typically was a four-hour flight lasted seven. I timed the fuel burn from the aux tanks to confirm I could make it, and I was ready to land at the first indication of engine problems. Everything stayed in the green with no signs of engine distress and I landed safely in Greenville. Feel free to challenge my decision, but my risk calculator said to fly home. The decision paid off because it wasn’t a quick fix. I later read Mike Busch’s book on Airplane Ownership (the Savvy founder) and he emphasizes “owner first, airplane second” in these situations. That’s a great mantra to remember from a maintenance and safety point of view.

On the ground in Greenville, I opened the cowl and saw that the cable operated correctly and there was no oil outside the engine. The next day my IA, Ted, pulled the prop and sent it and the governor out for evaluation and a flush. They came back in spec. The most likely culprit was a failed gear, shaft, or key that drives the governor off the camshaft inside the engine. They can fail, and the engine will keep running, but this prop will spring to fine pitch for lack of oil pressure differential. I’ll never know the cause because I pulled the engine off the airplane, dumped it in a crate, and sent it out as a core for a new Lycoming factory-remanufactured engine. Having two field overhauls since 1962 and lots of old parts with dubious serviceability, I opted for new to swing that new prop.

Ted is an A-plus guy. He teaches me how to work on the airplane and get oil under my fingernails, and he lets me stay in “hangar queen corner” as long as I need. Over four months, I took everything off the firewall and replaced it all with new or overhauled parts. The factory reman comes with a new carburetor, mags, harnesses, and plugs. I overhauled the engine mount and baffles. I replaced the shock mounts, the fuel pumps, the oil lines, the fuel, lines, and all the SCAT tube. I bought a new fully wired cannon plug from Comanche Gear, a new vacuum pump, and added a new dual exhaust system. I even added KoolMat to the firewall. But the best decision I made was to install an EDM-830 engine monitor. It was an easy job and provided so much information for optimizing the engine’s operation. The engineer in me geeked out on all the data in the display.

In classic “while-you’re-at-it” mode, I pulled the panel, cleared the rats’ nest of old wires and unused hardware, and replaced the entire vacuum system with new-make. Call me old school, but I still like vacuum gyros’ redundancy and low cost. Garmin G5s weren’t yet interfacing with my old Century IIB and never crossed my mind. I was also running low on cash.

By the start of 2019, I was flying behind a new engine, a new prop, and more than adequate avionics when my mother in Naples, FL, started to succumb to Alzheimer’s. To keep her comfortable, my partner Deb and I flew the Beast there every other weekend and whenever she needed us. It was some of the most challenging weather I have experienced, but it was rewarding. Deb and I and the Beast were at our best. But as Covid enveloped the world, my mom passed before it stopped the flights. I was thankful for that and marched towards an early retirement holed up in my Greenville condo.

When I turned in my corporate badge and laptop and said goodbye to a stressful but rewarding career, I decided to tackle AD 77-13-21-part A in a big way. During my first week as a retired guy, Ted and I brought the Beast into hangar queen corner, put it up on jacks, and he said, “well, just take it all apart and don’t lose anything.” I went into full medieval slash-and-burn mode and left nothing in the wheel wells except the newer gear conduits. At this point, my best friends were Ted, my camera, Matt Kurke’s manual and tools, and the parts manual. I found a lot of bolts and bushings that no longer met spec and replaced those with new-make. I bought two of Matt’s new old stock drag links and rod ends modified with the grease vents. I replaced all the oleo seals and wipers. I stripped, primed, and painted every part, including the wheel wells. One magical moment was when I saw the main trunnion webs in perfect condition. I sent them to Matt for dressing that little hole and web edge to prevent cracks from forming. When everything was ready for installation, I took a fun photo of all the left main gear parts before assembly as a reminder of the complexity and beauty of the Comanche gear. I carefully worked through the rigging procedure and was rewarded with an in-spec up-limit torque and a mighty thump as the new springs pulled the gear over-center into down and locked. While waiting for parts to come in, I opted to rip out the headliner and add new Alpha Aviation shoulder harnesses for the front seats. Extra stringers are riveted into the top of the fuselage to carry that load. I also replaced the original windows with 1/4-inch-thick acrylic. It’s a tight fit into the upper channel for the side windows and required substantial motivation to seat correctly. And with that, the Beast was flying again. Without a headliner, little bits of insulation would drop onto my head from time to time but I would solve that problem later.

I was proud of the mechanical integrity of the airplane now but very embarrassed by the paint and interior. I had some quotes for top-shelf interior replacements, but I settled on a more affordable leather Airtex kit I could install myself. I called Airtex and placed an order for the headliner, side panels, carpet, and leather seat upholstery. All components were made to order and came at separate times. The first to arrive was the headliner. Thinking gut job all the way, I removed all the original fiberglass insulation and replaced it with Airtex’s soundproofing and insulation material. It adds about 10 lbs to the empty weight, but there is a noticeable solidness to the feel of the airplane, especially the door. I had fun installing the headliner but making the first cuts and gluing the first edges were a bit stressful. Attention is required to keep all the seams straight as the fabric gets stretched. I stripped the side panels to bare metal and repaired all the extra holes and bends those 60 years of avoiding proper panel removal can create. I went back to the original factory clips to install them. Thanks, Webco. With the upholstery done except for the seats (still six weeks out), I was back in the air with my partner Deb headed to Boise, Idaho, for the summer by way of New Orleans, Austin, and Santa Fe.

The seat upholstery was ready while I was in Boise. I had it shipped there and spent the next couple of months ripping off the old stuff, including the awful straw batting, repairing the seat springs, and repainting the frames in the backyard of the Airbnb I was renting. I then coerced the glove-tight leather with sewn-in high-density foam onto those frames. Patience and a deft use of hog ring pliers are the only skills required. With the first seat done, it was clear that the quality of the materials and workmanship of the Airtex kit was as good as any upholstery job I’d seen. One at a time, I recovered the seats and put them in the airplane, blending old and new while flying ’73P around the west. What a difference new foam makes. The Airtex product provides support and comfort, and I’m thrilled with the result.

Finally, the old was only on the outside. I had long anticipated the need to repaint the Beast. In 2020 I got a quote and secured a spot in line at Boss Aircraft Refinishers in Salisbury, NC. The call came in mid-April 2022. “Drop off your airplane the first week of May.” No problem, except I was still in Boise, having decided to reside there. It was the perfect time to notice a serious fuel leak in the top of the left main tank. I leafed through the logs to discover the other three tanks had been replaced, but the left was original. It was one of the last non-aluminum parts from 1962 to survive. John at Webco quipped, “you certainly got your money’s worth.” With a fresh annual under my belt and a new tank on order (12 weeks out), Deb and I launched for Salisbury, NC, by way of Sedona, AZ, and Bentonville, AR, two places that are a must to visit. We also stopped for cheap fuel, an excellent line guy, and a redolence you can only find in the cattle capitol of Texas, Hereford. It was a great photo to send to friends to show them what they were missing. At 11,000 ft over the flatness of central Texas, Deb was able to make dinner reservations in Bentonville on Open Table via her cell phone. What hath God wrought?

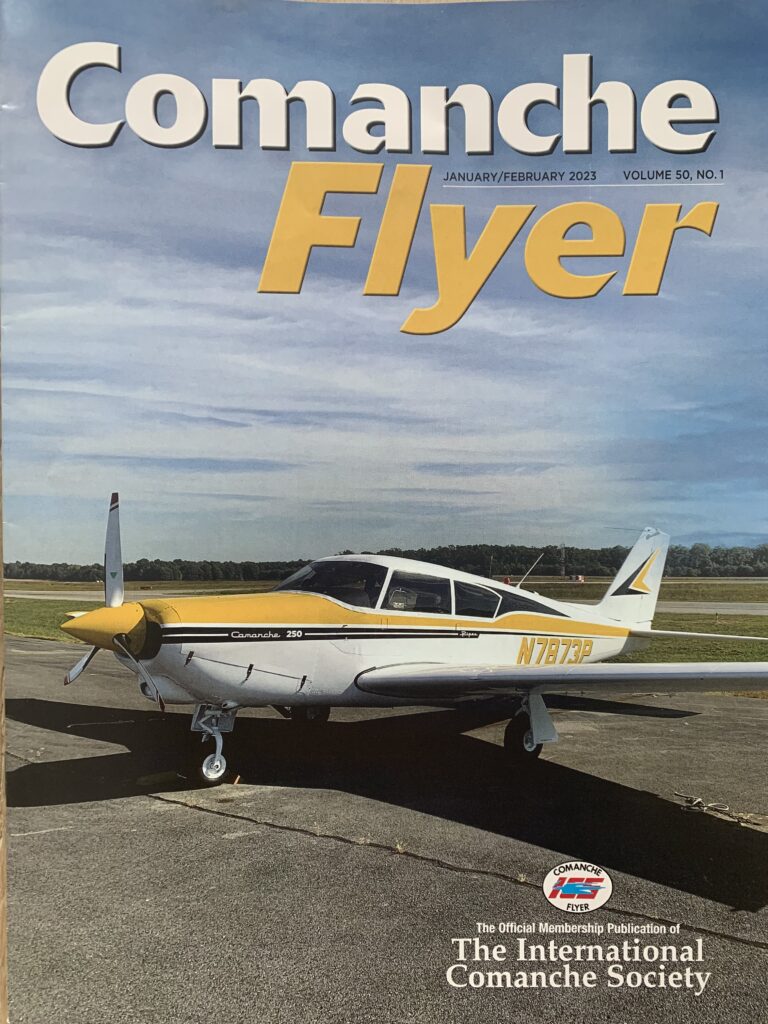

In light rain and with lowering visibility, ’73P landed at Salisbury, NC for Bill at Boss to start the repainting process a few days later. I wanted to use one of the classic Piper schemes, and Bill had done a Comanche he proudly displayed on his web gallery. “I want that one, Bill … just make it yellow.” His incredible team made it happen. They verified everything that worked or didn’t and then masked the windows and prop and chemically stripped the Beast. The team then disassembled, mechanically stripped, washed, etched, re-masked, and primed the aircraft. I was getting regular photos of each step from Bill and was impressed with the thoroughness of the process. The base coat was next, followed by reassembly, masking the trim scheme, and another disassembly. The trim colors and N-number were last. Bill’s team balanced the control surfaces, reassembled the airplane, buffed out odds and ends, jacked it up, swung the gear, verified everything worked, and signed the log. They earned the paycheck. It is an extensive process, and at any phase, an underlying problem can be revealed, requiring back-ordered parts that take your project out of line for a while. Fortunately, I had been through the airplane in detail and had literally flown the paint off, so I was confident there were no surprises. Still, Bill found and repaired two small cracks in that right wing skin and suggested replacing the cracked plastic tail fairings. I accepted all his advice. Customer communication during the process was exceptional and the team showed great pride in their work.

The rollout of the Beast was an emotional moment for me. It’s my forever airplane. After letting the paint cure for another month, I revealed the Beast at Triple Tree, SC, on a perfect Saturday morning. In the seven years I’ve owned it, ’73P has been on jacks for about eight months and flying all over the country the rest of the time. By replacing aging parts with the latest tech available, I’m down to only four repetitive ADs from a notoriously long list. Except for an intermittent ground (another tale worthy of Agatha Christie), the Beast never let me down and always got me home safely. Only now, The Beast is a new 1962 Comanche with my fingerprints on every part.